On a cold December in 2004, a newcomer began knocking on doors in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, introducing himself not as a politician in waiting but as a church planter.

“I’m starting a church next month,” he told residents, inviting them to hear a vision that stretched well beyond the pulpit. Twenty years later, that living-room pitch has become a 4,000-member congregation drawing people from 25 counties. It was proof, in his mind, that sustained, local, values-driven organizing can move mountains. It’s also, he insists, a working prototype for political power in eastern North Carolina.

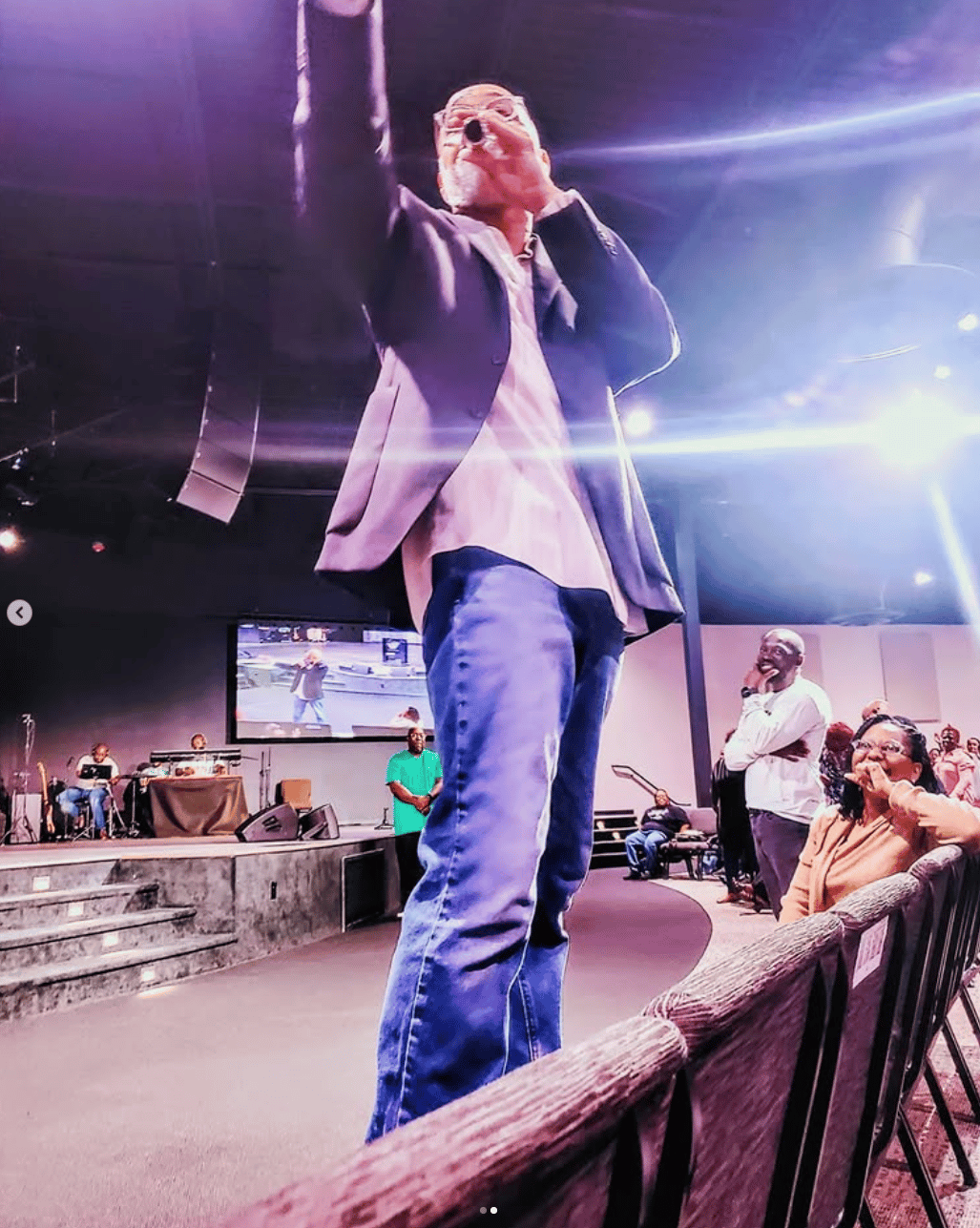

Pastor James Gailliard didn’t arrive by accident.

Trained to plant churches across the U.S. and in South Africa, he had been conducting post-apartheid ministry work when a North Carolina pastor asked him to train clergy back home. He came, fell hard for the east, and stayed. The choice was pastoral, but it was also strategic: Gailliard is a devotee of what he calls “the theology of place,” the belief that where you serve matters as much as how.

He turned down big-city pulpits because Rocky Mount was the assignment, spiritually, civically, and politically.

The church grew because it was built like an institution rather than a personality brand: vision and mission statements; core values; an evangelism plan; clear lanes for service. It also grew because the ministry reflected the needs of the people in front of him: education gaps, health disparities, food insecurity, economic inequity.

In Gailliard’s universe, church is more than just a Sunday event. And for members at Word Tabernacle, voter registration isn’t a suggestion. It’s a requirement of membership. He frames it not as partisanship but as discipleship.

God, he says, cares about schools, hospitals, housing, and safety.

Pastor Gailliard speaks with North Carolina Supreme Court Justice Anita Earls.

If the story ended there, it would be a familiar Southern saga. A charismatic pastor revitalizes a community. But Gailliard’s next chapter sharpens the point. In 2016, after a local school board dispute and a dismissive encounter with the sitting state representative, he decided to run for the North Carolina House.

The first race was a crash course launched late in the election cycle. The district was redrawn. He ran again and won—then again, and again, as the lines kept shifting. Across four campaigns from 2016 to 2022, he won twice and lost twice, never in the same district.

Redistricting, he notes dryly, had a way of moving the goalposts, often to the detriment of Black representatives in the east.

What these campaigns taught him is the cornerstone of his political philosophy. Not all Democratic messaging travels. East of I-95, he argues, candidates win by speaking in a vernacular rooted in community priorities. They win by talking about public education, health care access, local economics, housing, and safety and by resisting the temptation to import national scripts that don’t fit the terrain.

He is blunt about the arithmetic.

In rural precincts, a moderate, locally fluent Democrat who votes with the party 90 percent of the time is a victory compared to the alternative. Insisting on ideological purity in places that don’t share the cultural priors is, in his view, just another way of surrendering power.

That pragmatism is not a retreat, he says. It's a strategy.

Gailliard contends that Democrats have been losing the messaging battle on schools, most notably around vouchers and “opportunity scholarships,” because they’ve failed to meet people where they are. His debate with voucher proponents is simple. Fully fund public schools, where the vast majority of North Carolina’s children learn, and then let’s talk about the rest.

He believes the party’s brightest future in the east runs through trusted local messengers, like pastors, teachers, civic leaders, who can frame policy as moral choices, not partisan gamesmanship.

If that sounds like a playbook, that’s because he wrote one.

For Kamala Harris’s 2024 operation, Gailliard developed a faith-and-civic engagement toolkit. He calls it FACE. Unfortunately, he believes the party never fully grasped how it could be used.

In his eyes, the premise is disarmingly obvious, when you think about it. North Carolina has more churches than nearly any other state, and they are the only organized, trusted institutions present in every county. The buildings are there. The human capital is there. What’s missing is a disciplined, year-round program that equips clergy and lay leaders to organize their precincts.

The FACE model begins with adoption. Churches take responsibility for specific precincts, not abstract counties. It then shifts to what he dubs “micro-canvassing,” small, recurring conversations in community spaces, like fellowship halls, barber shops, and rec rooms, where eight to a dozen neighbors talk through the issues that actually shape their lives.

Under the Gailliard formula, you don’t start by asking for votes. You start by building literacy on the policy questions that confuse people or divide them: school vouchers, health care, public safety, immigration in farm towns. Each topic comes with a script, questions to ask, and a moral frame.

Pastors get sample sermons they can contextualize for their flock. Volunteers learn poll chaplaincy, such as how to be a visible, calm authority at voting sites when tensions rise. In his county’s last election, he recalls, Republican volunteers parked German Shepherds and pit bulls by their table.

Clergy collars have a way of quieting that.

Layered over the precinct work is the candidate’s own granular math. In his current Senate bid, Gailliard is methodically visiting all 54 precincts in the district. He knows the target vote number in each one. He knows which churches can help deliver it. And he knows what to say in Rocky Mount or Louisburg that won’t land in Durham and vice versa. This, in his telling, is the difference between retail politics and relational politics.

Then finally, there's this biggie. He is not afraid to say the quiet parts aloud.

He worries that national Democrats often rely on outdated assumptions about which churches matter and how faith shows up in Black communities. He bristles at the way Republicans have claimed a monopoly on religion while painting Democrats as secular elitists. And he is candid that some white progressives have blind spots when it comes to Black priorities.

None of that, in his mind, is cause for abandonment. It is just a call to organize differently.

In the midst of all of this, Gailliard’s personal life hums in the background. It's a blended family of high achievers spread from Chapel Hill to San Francisco. But even these details fold back into the thesis underneath it all: life is local, and leadership is service.

The Gailliard Family

Ask him what success looks like and he’ll tell you it’s measurable. If his model can move four points in a tough eastern district, people will notice. But the real victory is cultural.

It’s a party that finally understands what the East is asking for.

Images courtesy of Pastor James Gailliard.